Author David Margolick 1998 Vanity Fair

Southern trees bear a strange fruit, Blood on the leaves and blood at the root, Black body swinging in the Southern breeze, Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.

Pastoral scene of the gallant South, The bulging eyes and the twisted mouth, Scent of magnolia sweet and fresh, And the sudden smell of burning flesh!

Here is a fruit for the crows to pluck, For the rain to gather, for the wind to suck, For the sun to rot, for a tree to drop, Here is a strange and bitter crop.

As Billie Holiday later told the story, a single gesture by a patron at New York's Cafe Society, in Greenwich Village, changed the history of American music in early 1939, the night when she first sang "Strange Fruit."

Cafe Society was New York's only truly integrated nightclub outside Harlem, a place catering to progressive types with open minds. But Holiday was to recall that even there she was afraid to sing this new song, and regretted it, at least momentarily, when she first did. "There wasn't even a patter of applause when I finished," she later said. "Then a lone person began to clap nervously. Then suddenly everyone was clapping."

The applause grew louder and less tentative as "Strange Fruit" became a nightly ritual for Holiday, then one of her signature songs, at least where it could be safely performed. And audiences have continued to applaud this disturbing ballad, unique in Holiday's oeuvre and in the American popular-song repertoire, as it has left its mark on generations of writers, musicians, and listeners, both black and white. The late jazz writer Leonard Feather once called "Strange Fruit" "the first significant protest in words and music, the first unmuted cry against racism." Jazz musicians still speak of it with a mixture of awe and fear—"When Holiday recorded it, it was more than revolutionary," said the drummer Max Roach—and perform it almost gingerly. "It's like rubbing people's noses in their own shit," said Mai Waldron, the pianist who accompanied Holiday in her final years.

"Frankly, I don't think anybody but Billie should do it. I don't think anybody can improve on it."

A few years back a British music publication, Q Magazine, named "Strange Fruit" one of 10 songs that actually changed the world. And like any revolutionary act, it encountered great resistance. Holiday, like the black folksinger Josh White, who began performing it a few years after Holiday did, was abused, sometimes physically, by irate nightclub patrons. Columbia, the company that produced Holiday's records, refused to touch it; even progressive radio stations would not play it. And again like revolutionary acts, the song has generated its fair share of mythology, none more enduring than Holiday's often repeated claim that she partly wrote it herself or had it written for her.

"Strange Fruit" marked a watershed, praised by some, lamented by others, in Holiday's evolution from exuberant jazz singer to torch singer of lovelorn pain and loneliness. Some of the song's sadness seems to have stuck to her ever after. "She really was happy only when she sang," the jazz critic Ralph J. Gleason wrote. "The rest of the time she was a sort of living lyric to the song 'Strange Fruit,' hanging, not on a poplar tree, but on the limbs of life itself.

In recent years many musicians—from Carmen McRae to Nina Simone to Sting to Dee Dee Bridgewater to Cassandra Wilson—have recorded "Strange Fruit," each cut an act of courage, given Holiday's hold over it. (That might not apply to 101 Strings, which omitted the lyrics in its 1973 orchestral version.) The song continues to pop up in the most obscure places. The Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Leon Litwak uses it in his classes at Berkeley. It's what Mickey Rourke put on the turntable to seduce Kim Basinger early on in Adrian Lyne's 1986 film Nine 1/2 Weeks. (Predictably, it failed miserably as mood music.) The song was a staple of the anti-apartheid circuit in Europe. Khallid Muhammad, Louis Farrakhan's notoriously anti-Semitic former national spokesman, quoted it in a speech cataloguing America's racist past—unaware, apparently, that it was written by a white Jewish schoolteacher from New York City.

I wrote "Strange Fruit" because I hate lynching, and I hate injustice, and I hate the people who perpetuate it. —Abel Meeropol (a.k.a. Lewis Allan), 1971.

Billie Holiday, who was only 24 years old in 1939, had enough experience with racism by that time to call herself "a race woman." But while hard knocks helped her infuse a unique mixture of resilience, defiance, and shrewdness into the often banal lyrics she sang, they had never influenced her choice of material, at least not until "Strange Fruit" came along.

Holiday's 1956 "autobiography"—written by William Dufty (and known, like the 1972 film biography, as Lady Sings the Blues, though she had wanted to call the book Bitter Crop)—offers an account of the origins of "Strange Fruit" that may set a new record for most misinformation per column inch. ("Shit, man, I never read that book," she later said.) But in fairness to Dufty, she'd been peddling many of these myths for years. "The germ of the song was in a poem written by Lewis Allen [sic]," the book claims. "When he showed me that poem, I dug it right off. It seemed to spell out all the things that had killed Pop," Dufty quotes her. According to Holiday, her father was exposed to poison gas as a soldier during World War I and died of pneumonia in 1937 after several segregated southern hospitals refused to treat him. "Allen, too, had heard how Pop died and of course was interested in my singing. He suggested that Sonny White, who had been my accompanist, and I turn it into music. So the three of us got together and did the job in about three weeks."

Abel Meeropol, who is often remembered today for raising the two orphaned sons of the executed atomic spies Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, recalled things very differently. An English teacher at De Witt Clinton High School in the Bronx for 27 years, Meeropol had led two other, parallel lives. One was as a political activist: he and his wife were closet Communists, donating a percentage of their earnings to the party. (The F.B.I. maintained that he had "been identified by reliable informants" as a party member until 1947, though it followed him for 23 years after that.) The other was as a poet and songwriter. He wrote incessantly— poems, ballads, musicals, plays, usually using the nom de plume "Lewis Allan," the names of his two biological children, neither of whom survived infancy. Apart from "Strange Fruit," he is best known for writing the lyrics of "The House I Live In," a paean to tolerance sung by Frank Sinatra in an Oscar-winning short subject in 1945.

Lynchings—in which blacks were murdered with unspeakable brutality, often in a carnival-like atmosphere, then hanged from trees for all to see—were rampant in the South during Reconstruction and beyond, but had grown relatively rare by the late 1930s. (As the recent murder of a black man in Jasper, Texas, attests, they never completely stopped.) The N.A.A.C.P., until as late as 1941, had routinely attempted to push Congress—always to no avail—to enact federal antilynching legislation. Somewhere around 1935, Meeropol, in his early 30s at the time, saw a photograph of a particularly ghastly lynching. "It ... haunted me for days," he later recalled. He wrote a poem about it, one which was originally to have appeared in the Communist journal The New Masses but first saw print— as "Bitter Fruit," by Abel Meeropol—in the January 1937 issue of The New York Teacher, a union publication. Meeropol set the poem to music, and in the late 1930s the song was regularly performed in left-wing circles—by the Teachers' Union chorus, by a black singer named Laura Duncan (at Madison Square Garden), by a quartet of black singers at a fund-raiser for the anti-Fascists during the Spanish Civil War. As it happened, the co-producer of that show, Robert Gordon, was also directing the first-floor show at the new Cafe Society, which had opened in late December 1938. The featured attraction: Billie Holiday.

One of the first numbers we put on was called "Strange Fruit Grows on Southern Trees," the tragic story of lynching. Imagine putting that on in a night club! —Barney Josephson, 1942.

Cafe Society—"a nightclub to take the stuffing out of stuffed shirts," where leftwing W.RA. types did the murals and a simian-looking Hitler hung from the ceiling near the foyer—was unusual even for New York City. Billed as "the wrong place for the Right people," it mocked the empty celebrity worship, right-wing politics, and racial exclusion of places like the Stork Club. At Cafe Society, the doormen wore rags and ragged white gloves, blacks and whites fraternized onstage and off, and the politics were somewhere left of the New Deal. When Eleanor Roosevelt made what might have been her only foray into a New York nightclub, it was allegedly to Cafe Society that she went.

Located on Sheridan Square (a second Cafe Society soon opened on 58th Street near Park Avenue), it was the brainchild of Barney Josephson, a shoe salesman with leftist sympathies; its patrons, the historian David W. Stowe has written, consisted of "labor leaders, intellectuals, writers, jazz lovers, celebrities, students and assorted leftists." As Michael Denning of Yale has put it, Cafe Society represented a unique synthesis of cultures, blending the politically radical cabarets of Berlin and Paris with the jazz clubs and revues of Harlem. Nelson Rockefeller, Charlie Chaplin, Errol Flynn, Lauren Bacall, Lillian Heilman, Langston Hughes, and Paul Robeson hung out there; Lena Horne, Teddy Wilson, Sarah Vaughan, Imogene Coca, Carol Channing, and Zero Mostel performed there. It was probably the only place in America where "Strange Fruit" could have been sung and savored.

One day in early 1939, Meeropol—who had never met Holiday before and knew nothing about her father—sat down at Cafe Society's piano and played her the song. Neither Tin Pan Alley nor jazz, it was closer to the political theater songs of Marc Blitzstein and other leftist composers. But it was utterly alien to her, and, to Meeropol at least, Holiday appeared unimpressed. "To be perfectly frank, I didn't think she felt very comfortable with the song, because it was so different from the songs to which she was accustomed," Meeropol later wrote. She asked him but one question: What did "pastoral" mean?

Josephson, too, said that Holiday "didn't know what the hell the song meant," and adopted it only as a favor to him; not until several months later, when he spotted a tear running down her cheek during one performance, did he feel the song had sunk in. ("But I gotta tell you the truth," Josephson liked to say. "She sang it just as well when she didn't know what it was about.") To be sure, Holiday was in some ways unsophisticated, famous for reading nothing more serious than comic books. Still, it's hard to believe she was as oblivious as Josephson claimed. Indeed, Meeropol later said that when Holiday introduced the song "she gave a startling, most dramatic, and effective interpretation ... which could jolt an audience out of its complacency anywhere. ... Billie Holiday's styling of the song was incomparable and fulfilled the bitterness and shocking quality I had hoped the song would have."

We used to give Holiday cash, especially when she was in trouble, right out of the cash register in the store. We never really kept a record of it."

No one ever tampered with Meeropol's words. But Arthur Herzog, who wrote another famous song often misattributed to Holiday—"God Bless the Child"—claimed that an arranger, Danny Mendelsohn, was really responsible for the final sound.

One story has it that Holiday's mother objected when she began singing "Strange Fruit." "Why are you sticking your neck out?" she asked.

"Because it might make things better," Holiday replied.

"But you'll be dead," her mother insisted. "Yeah, but I'll feel it. I'll know it in my grave."

Josephson, who called the song "agitprop," decreed elaborate stage directions for each performance of "Strange Fruit." Holiday was to close each of her three nightly sets with it. Before she began, all service was to cease. Waiters, cashiers, busboys—all were immobilized. The room went completely dark, save for a pin spot on Holiday's face. No matter how thunderous the ovation, she was never to return for a bow. "My instruction was walk off, period," Josephson later said. "People had to remember 'Strange Fruit,' get their insides burned with it." But as Heywood Hale Broun, the longtime CBS newsman, remembered it, Holiday sang "Strange Fruit" in the middle of the set, following it up quickly with something light in order to cut the tension. "After we'd oohed and aahed in our kind of liberal way, the band would hit a sharp chord and then go into 'Them There Eyes,'" Broun said.

She came out [of Cafe Society]. She was screaming, "Renie, I tried to kill him, I tried to kill him, I tried to... "And she told me then that there was this fella—a white man from Georgia, you know, one of those Georgia crackers—who was sitting ringside and drinking, and Lady was doing "Strange Fruit." And when Lady was on her way out of the club, he yelled, "Come here, Billie.''She went, thinking he wanted to buy her a drink, but he said, "I want to show you some strange fruit," and ... well, he made this very obscene picture on his napkin, and the way he had it, honey, it was awful! And she picked up the chair and hit him on the head, and before it was over, she showed him, honey, because she went crazy. I mean that she was sweeping up the floor with this man, honey, and they said—the owner and bouncer at Cafe Society said, "Go on, Lady. We'll take care of him," and they threw him out right on his ears. —Songwriter Irene Wilson, 1971.

To many, "Black and Blue," immortalized by Louis Armstrong, with lyrics written in 1929 by Andy Razaf, was the first black protest song aimed at a largely white audience. White songwriters approached civil rights tentatively; Irving Berlin referred obliquely to lynching in "Supper Time" (a song Ethel Waters made famous), but before Meeropol and Holiday came along, no one had ever confronted the subject so directly.

Reactions varied. Variety conceded that "Strange Fruit" had "an undefined appeal" but called it "basically a depressing piece." Some patrons voted with their feet. "Lots of people walked out on the song because they said 'we don't call this entertainment,'" Josephson told Linda Kuehl for a never completed biography of Holiday. "I remember a time a woman followed Billie into the powder room. Billie was wearing a strapless gown and she tried to brush the woman off. The woman became hysterical with tears—'Don't you sing that song again! Don't you dare!'—she screamed and ripped Billie's [gown]." It turned out that as a young girl the woman had seen "a black man tied by the throat to the back fender of a car, dragged through the streets, hung up, and burned," recalled Josephson. She'd thought she'd come to Cafe Society for a good time, not to relive a childhood nightmare.

More often than not, though, people began requesting the song, and it became part of Holiday's routine, even though it made her sick to perform it. "I have to sing it," she once said. "'Fruit' goes a long way in telling how they mistreat Negroes down South."

Soon, Cafe Society began advertising not just Holiday—referred to in press accounts as the "buxom, colored songstress" or the "sepian songstress"—but the song itself. HAVE YOU HEARD? "STRANGE FRUIT GROWING ON SOUTHERN TREES" SUNG BY BILLIE HOLIDAY, an advertisement in The New Yorker asked in March 1939.

But Columbia records, apparently fearful of antagonizing southern customers, wanted no part of recording the song. So Holiday persuaded Milt Gabler, an entrepreneur who'd started Commodore Records, a small company run out of a music store on West 52nd Street, to do it instead.

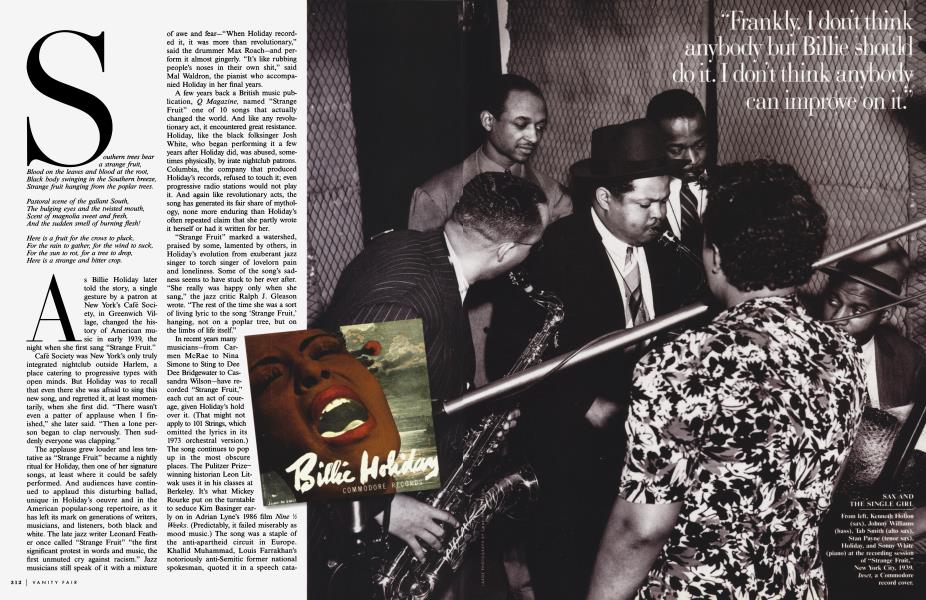

On April 20, 1939, Holiday and the musicians—Sonny White on piano, Frankie Newton on trumpet, Tab Smith on alto sax, Kenneth Hollon and Stan Payne on tenor sax, Jimmy McLin on guitar, John Williams on bass, Eddie Dougherty on drums—made what was to become the first and most famous recording of "Strange Fruit." At a dollar apiece, Commodore's 10-inch records went for three times the going rate. Concerned that customers would feel shortchanged by too brief a cut, Gabler had White improvise his now familiar, haunting overture; given "Strange Fruit"'s dramatic close, one could hardly tack on anything at the end.

"All of a sudden something stabs me in the solar plexus and I was gasping for air. That's what art can do."

One day last winter, Gabler, now 87 years old, played "Strange Fruit" for me at his home in New Rochelle, New York. He fetched an antique LP from his archive, then laid it down with shaky hands on an ancient turntable. Amid the scratches and static emerged Billie Holiday's utterly distinctive sound. Here, she is grim and purposeful, yet still with a lovely lightness to her. There is no weepiness, nor histrionics. Her elocution is superb, with a hint of a southern accent; her tone is somehow languorous but unflinching, raw yet smooth, youthful yet worldly. The overt editorializing is minimal, and the sentiment isn't grief so much as contempt, as she spits out references to southern gallantry and the aroma of the magnolias. But the intensity mounts until the last word of the song: "crop." She sings it on a strangely unresolved note, dangling it back and forth like the dead black man swinging on the branch.

Gabler says he gave Holiday $500 for the four songs she recorded that day ("Fine and Mellow" among them), and $1,000 later. How much she eventually earned he could not say. "We used to give her cash, especially when she was in trouble, right out of the cash register in the store. We never really kept a record of it."

One of the saxophonists, Kenneth Hollon, later said the record sold 10,000 copies in its first week. Meeropol, who had failed to copyright the song, learned it had been recorded only when a friend brought him a copy. He ultimately got standard royalties: two cents per record, one for the words, another for the music. At least initially, Meeropol collected more grief from "Strange Fruit" than receipts. During a 1940 state probe of Communist "subversion" in New York's public schools, he was asked whether the Communist Party had ever paid him for the song or if he'd donated the proceeds to the party. But the pennies mounted: according to Bob Golden of Carlin America, the longtime publishers of "Strange Fruit," the Meeropols, father and sons, eventually earned more than $300,000 from it.

This is about a phonograph record which has obsessed me for two days. It is called "Strange Fruit" and it will, even after the tenth hearing, make you blink and hold to your chair. Even now, as I think of it, the short hair on the back of my neck tightens and I want to hit somebody. I know who, too. —Samuel Grafton, the New York Post,October 1939.

'Strange Fruit" made it to No. 16 on the charts in July 1939 and was widely publicized. The New Masses called it "the first successful attempt of white men to write blues." In a piece entitled "Strange Record," Time described "Strange Fruit" as "a prime piece of musical propaganda" for the N.A.A.C.P., and printed the first verse of "Allan's grim and gripping lyrics." ("Billie Holiday is a roly-poly young colored woman with a hump in her voice," the article began. "She does not care enough about her figure to watch her diet, but she loves to sing.") But surely the most extravagant praise came from Samuel Grafton, a columnist for the New York Post. "If the anger of the exploited ever mounts high enough in the South, it now has its Marseillaise," he wrote.

Proponents of federal anti-lynching legislation urged that copies of the song be sent to Congress. Within a few years "Strange Fruit" became the title of Lillian Smith's famous 1944 anti-segregation novel. Holiday's claim that Smith, a southerner herself, told her the song had inspired her to write her novel is fanciful. But Smith acknowledged "Lewis Allan" on the title page, and went to Cafe Society once to hear Holiday sing. (Holiday seemed stoned to Smith when she visited her backstage.)

Jazz purists never liked "Strange Fruit," nor what they thought it did to Holiday. "Perhaps I expected too much of 'Strange Fruit,' the ballyhooed ... tune which, via gory wordage and hardly any melody, expounds an anti-lynching campaign," a Down Beat critic wrote. "At least I'm sure it's not for Billie." More famously, John Hammond, who had discovered Holiday as a teenager and produced her records at Columbia, called the song "the beginning of the end for Billie" and "artistically the worst thing that ever happened to her." To him, Holiday had simply gone too serious. "The more conscious she was of her style, the more mannered she became," he later said. By taking herself so seriously, she suffered artistically and lost her sparkle. Holiday, he lamented, had become the darling of left-wing intellectuals and homosexuals; fortunately, whites had never caught on to Bessie Smith in the same way.

After performing at Cafe Society for two years, Holiday left. (Hounded by the Red-baiting of J. Edgar Hoover and his covey of favored columnists, Josephson was essentially forced to sell his clubs in 1949.) Some other New York clubs refused to let Holiday sing the song, prompting her to specify by contract that she could perform it if she chose. That didn't guarantee anything. A patron at Jimmy Ryan's on West 52nd Street once requested it, only to see Holiday come back afterward almost in tears. "Did you hear that bartender ringing the cash register all through?" she asked him. "He always does that when I sing."

"Strange Fruit" has "a way of separating the straight people from the squares and cripples," Holiday's autobiography states. She recalled the time a woman in Los Angeles asked her to sing "that sexy song" she was so famous for—"you know, the one about the naked bodies swinging in the trees." (She refused.) Another time, at a club outside Los Angeles (where Lana Turner regularly asked her to perform it), a young white man hurled racial epithets at her. "After two shows of this I was ready to quit," she later recalled. "I knew if I didn't the third time round I might bounce something off that cracker and land in some San Fernando ranch-type jail." Instead, Bob Hope, who was at the club with Judy Garland, badgered the heckler until he left.

In interviews, Holiday said that whenever she performed "Strange Fruit" in the South there was trouble. She told one newspaper that she was driven out of Mobile, Alabama, for trying to sing it. In fact, Holiday made few southern tours, and there's little evidence that she sang "Strange Fruit" when she did. Stories of jukeboxes carrying "Strange Fruit" down South being smashed seem fanciful, if only because Commodore Records probably didn't circulate that far.

Claims that the song was banned from the radio are equally hard to document, but not hard to believe; radio stations played few records then, and rarely anything controversial. "WNEW [in New York] has been trying to get up the courage to allow Billie Holiday, singing at Cafe Society, to render the anti-lynching song—'Strange Fruit Growing on the Trees Down South' —on one of the night spot's regular broadcasts," the New York Post reported in November 1939. "Station turned thumbs down a week ago, but approved the number for last night's airing. Then it said 'no' again, but has agreed to let Billie sing it tonight at 1 o'clock." (According to one published report, the song was also banned from the BBC.)

"You listened to every word; it was like watching water drop slowly from a faucet."

Albert Murray, the eminent historian of the blues, calls "Strange Fruit" a "dogood" hit, one that resonated far more with white liberals than with blacks. But Holiday sang the song for black audiences, including several performances at the Apollo Theatre in Harlem. Jack Schiffman, whose family ran the Apollo, says his father did not want Holiday to do so, fearing disturbances. But in his memoirs Schiffman described what happened when she did. "When she wrenched the final words from her lips, there was not a soul in that audience, black orwhite, who did not feel half strangled," he wrote. "A moment of oppressively heavy silence followed, and then a kind of rustling sound I had never heard before. It was the sound of almost two thousand people sighing."

She would get herself together to do that one. The others were kind of natural tunes, and she would spin them off the way she talked. This one was special. She had to do preparation for this one. —Pianist Mai Waldron.

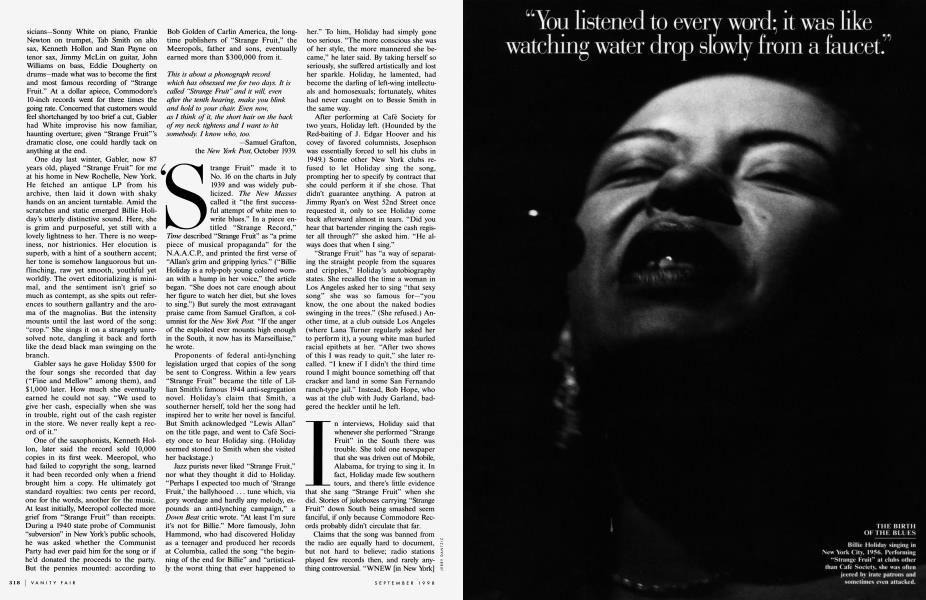

Until the end of Holiday's life, "Strange Fruit" remained a fixture in her performances, and wherever, whenever she sang it, it was an event. With every indignity she suffered, her passion for it seemed to grow; a racial snub she'd just suffered at a St. Louis nightclub, The New York Amsterdam Newsreported in 1944, explained why she sang the song "with so much fervor and smoldering hatred in her eyes." Actress Billie Allen-Henderson recalled how the maitre d' at New York's Birdland actually confiscated all cigarettes before Holiday began. "I was trying to be sophisticated and all of a sudden something stabs me in the solar plexus and I was gasping for air," Henderson said. "It was so deeply felt. She was ... 'unrelenting' is a good word for it. I thought, That's what art can do." Dempsey J. Travis, a former jazz musician and author of several books, heard a decrepit, dissipated Holiday sing it several times on Chicago's South Side. "The words told the story, but her face never reflected any emotion," he said. "You listened to every word; it was like watching water drop slowly from a faucet.... It was as if she was singing 'Ave Maria' or 'Amazing Grace.'"

Holiday performed "Strange Fruit" on a European tour in 1954; that may have inspired a Parisian named Henri-Jacques Dupuy to translate it into French. But "Strange Fruit" proved just as unsettling abroad. "With all the troubles the French are currently having with coloured people in Indochina and North Africa, I do not think it will be possible to get a major recording of Mr. Dupuy's version," Rudi Revil, a French song publisher, wrote Meeropol.

Holiday's "autobiography," with all of its mistakes, appeared in 1956. Meeropol, while conceding that her tragic life may have led to some "lapses into fancy," claimed he won a pledge from the publisher, Doubleday, to delete all misinformation about "Strange Fruit" from subsequent editions of the book. (They nonetheless live on in the most recent paperback edition, published by Penguin in 1992.) One can only imagine how Meeropol reacted to the movie Lady Sings the Blues,for its fictions were far more egregious than anything Holiday ever cooked up. The film shows Diana Ross as Holiday encountering a lynching while touring the South; stricken by what she sees, she adopts a laserlike, knowing look—the look, presumably, of lyrics taking shape. The chords of "Strange Fruit" then sound, and Ross sings a bowdlerized version of the song, shorn of all of its most powerful images. The filmmakers paid $4,500 for the right to rape the lyrics.

Meeropol developed Alzheimer's disease in the late 1970s; his elder son played "Strange Fruit" for him in the nursing home, and when the record got too scratchy, he sang it to him. Even after the old man stopped recognizing anyone, he seemed to recognize it, and perked up when he did. When Meeropol died in 1986, it was sung at the memorial service.

In The Heart of a Woman, Maya Angelou recounts how, during a visit to Los Angeles in 1958, in a hoarse and raspy voice, Holiday sang "Strange Fruit" as a bedtime song for her son, Guy. "What's a pastoral scene, Miss Holiday?" the young boy interjected.

"Billie looked up slowly and studied Guy for a second," Angelou writes. "Her face became cruel, and when she spoke her voice was scornful. 'It means when the crackers are killing the niggers. It means when they take a little nigger like you and snatch off his nuts and shove them down his goddam throat. That's what it means. . . . That's what they do. That's a goddam pastoral scene.'"

Within a year, Holiday was dead. To some, the song remained uniquely hers. "Frankly, I don't think anybody but Billie should do it," said Dan Morgenstern, director of the Institute of Jazz Studies at Rutgers. "I don't think anybody can improve on it." But the song's power and appeal to a younger generation of performers only grew with the civil-rights movement, and as lynching became a metaphor for the American black experience rather than a direct threat.

Abbey Lincoln, who tackled "Strange Fruit" on her 1987 album, Abbey Sings Billie, said she had no trouble singing the song. Slavery's over and so is lynching, she said; her goal was not to dwell on black victimhood but to pay homage to Holiday herself. For Cassandra Wilson and Dee Dee Bridgewater, however, "Strange Fruit" has proved considerably more difficult.

Wilson, Down Beat's "Female Vocalist of the Year" two years ago, said that when she first heard "Strange Fruit," in her native Jackson, Mississippi, in the late 1970s, it "made my skin crawl." Many years had to pass before she felt she had the wisdom, the experience, and the courage to perform it. "That was a song that I always felt I had to get to," she said. One approaches it, she said, not by trying to outdo or enhance Holiday—a fool's errand by any definition—but by stripping the song bare. Holiday sometimes performed "Strange Fruit" almost punitively, to chastise an inattentive or unappreciative audience. Wilson, by contrast, said that because the song is so emotionally taxing for her she does it to reward audiences with whom she has established a special rapport.

Like Wilson, Dee Dee Bridgewater, whose album Dear Ella won two Grammys this year, first heard "Strange Fruit" while in her 20s. She, too, was profoundly moved by it; she, too, balked at singing it herself. But when she portrayed Holiday in a one-woman show in the mid-1980s, she had no choice. She subsequently included "Strange Fruit" in her concert repertoire, but only when she felt she had a sufficiently sensitive pianist—namely, a blind Dutchman named Bert van den Brink—accompanying her. Together, they performed it eight or nine times, always in Europe. Often, she cried as she sang it; sometimes, she choked on the ending. At least once, she couldn't finish.

Then there was Bridgewater's performance in Turin, Italy. "There was just dead silence, then this amazing roar," she recalled. "In that deadness, I just broke down. I was sobbing. I had to leave the stage." Shortly after that, she decided never to sing it again. "I just can't do it anymore," she said. "I just don't want to go there."